A few notes on the WireGuard Whitepaper

Table of Contents

Article Context and Motivation

I’m setting up a VPN for my home infrastructure. Last time I simply did it with pivpn, but I faced some issues for which I was ill-equipped. This time around I wanted to solidify my knowledge before trying anything, so I’m reading the whitepaper. Since I knew they would introduce concepts I’m truly unfamiliar with, I decided to pull out good ol’ Neovim to take some notes. These are my drafts, enjoy…

Initial Exploration

The fundamental question aka our starting point. What is WireGuard?

It’s covered in the first sentence but it spans three lines, so it’s quite long. I think I can summarize it in simpler terms but I won’t (yet), because while skimming through it I can already count 3 terms that I’m unfamiliar with! So let’s dig into those first while mapping out how they relate to the main point, and who knows, at the end we might have our own little definition.

Core Components and Concepts (I’m struggling with)

Three key aspects emerge from WireGuard’s (abstract) definition that warrant deeper investigation:

- a secure network tunnel operating at layer 3

- kernel virtual network interface

- The virtual tunnel interface is based on a proposed fundamental principle of secure tunnels: an association between a peer public key and a tunnel source IP address.

Understanding OSI Model and Tunneling

The opening sentence of the whitepaper states: “WireGuard is a secure network tunnel operating at layer 3”. I must admit I have to brush up on my OSI model knowledge here haha.

The Building Block of Network Communication

To understand tunneling, we first have to address the process of encapsulation. Which perfectly ties in to understanding wireguards’s operation at layer 3. I liken the process of encapsulation to chinese whispers, because of the similarity in sharing a massage accross layers while adding additional data. However, as we’re dealing with critical infrastructure in networking, we made sure that the additional data doesn’t result in any sort of distortion. With the reverse of that process called “decapsulation” which is where we go upstream instead of downstream in the OSI model. That brings us to wireguard’s operation at layer 3. This means that wireguard patiently waits during that process of encapsulation/decapsulation and actively adds its headers and encryption when it’s their turn to encapsulate/decapsulate!

Understanding Data Flow

It’s like a man carrying a letter (the data) inside an envelope (the packet), going down an apartment by use of an elevator and entering an apartment at each floor to do business. He gets additional signatures and informational data on his envelope after each visit. Once he gets down to ground level, he leaves the apartment complex to go deliver the envelope to someone else. The recipient does the opposite, and goes up this new apartment to ask for “directions” at each floor, based on the additional data that’s been added onto the envelope.

Network Tunneling: Beyond the Basics

Now about those tunnels. First of all I don’t like thinking of tunnels as connections or methods for secure/private communication as they’re sometimes referred to. Tunnels are simply a logical construct. The process of tunnelling actually means that we’re putting the packet from one protocol (the original data) inside a packet from another protocol (new packet). This only happens at a specific layer and is exactly what wireguard does (in-part).

Practical Application of Tunneling

To simplify this explanation and keep on with our previous example, we can think of the man going down the elevator and stopping at a specific apartment. But this time not just to receive additional signatures and informational data. But to actually get a new envelope with brand new data and signatures around it, in which he’ll put his previous envelope in! This is the concept of tunneling. Putting packets from protocol A inside packets from protocol B. As you can see this doesn’t fundamentally guarantee security or privacy in communications, but I must admit that it does keep the data somewhat obfuscated. But then again, this is just security through obscurity which has pretty much never worked out in the long term. This is why wireguard doesn’t simply rely on tunneling for its security posture. They actually make use of some kreeeeeezi cryptography, which we’re going to be covering later on.

Layer 3 Operations: The Performance Advantage

Final notes on the benefits of layer 3.

To understand why WireGuard set up shop at layer 3, we can simply look at how much more complexity and trouble, operating at a higher layer would cause. Let’s take the example of a VPN operating at layer 7, like OpenVPN for instance. Such protocols actually have to understand every single protocol they’re dealing with. Let’s say we have data from HTTP, FTP, RTP. We would have to process each protocol differently! Which would just add so much more complexity and create a mess, you can clearly see how this would reduce performance. Whereas with wireguard, when the data gets to layer 3, it has already been processed and converted into IP packets. So there’s no more processing to be done here, we just have to encrypt the data and tunnel it. This is what they mean when they say that WireGuard is protocol-agnostic.

Kernel virtual network interface

I’m not too knowledgeable on kernels (yet) so I won’t dwell on it. But now that I know that wireguard operates at layer 3, the fact that it’s been implemented at the kernel level as a virtual network in terface makes total sense and clarifies why it’s superior to other protocols in terms of security and performance. By being in the kernel space, it’s “closer to the metal” so data literally has to travel less over time and space to reach it. Which means wireguard is able to receive the data way earlier in communications than somethin like OpenVPN. When you think about the security implications of this, you have to understand that if your tunnel is waiting for data way up there at the user-space level and application layer. By the time you understand what’s going on, the data is already knee deep in your machine, and you’re effectively at its mercy.

Okay, upon further research, the fact that wireguard has been implemented at the kernel level is nothing more than a logical necessity, as all virtual network interfaces are handled by the kernel anyways. This is simply a given, as opposed to the layer 3 position which has been purposefully chosen for its security and performance benefits. Don’t get me wrong the decision to implement it as an interface goes hand in hand with the design choice of having it set up at layer 3. You can’t have one without the other. As typical userspace programs can’t reach anything below layer 4 without involving the kernel.

A quick general note about VPNs

As I’m reading this little section of the whitepaper, I have perplexity on the side to ask all of my questions. This has led me to have a breakthrough moment. VPNs are nothing more than cryptographic tunnels. The idea of a virtual private network, rubs me the wrong way. There’s no such thing as privacy on the information superhighway. However I do agree with the virtual network part, as tunnels don’t actually “exist”. But they merely serve as logical abstractions of an encrypted transportation mechanism.

Understanding WireGuard’s Core Security Principle

The virtual tunnel interface is based on a proposed fundamental principle of secure tunnels: an association between a peer public key and a tunnel source IP address.

Here is another statement that bothers me quite a bit, because while it presents a princilpe that adds a layer of security, it doesn’t quite paint the full picture. And if the wireguard protocol were to be implemented in such a simple way, it would actually expose itself to an attack vector, which I thought was an actual vulnerability. Until I figured out it wouldn’t work, because of the handshake mechanism that wireguard uses. We won’t dive into it now because that’s covered later in the whitepaper. But I think I should explain what they meant by this sentence, and how that led me to believe there was a potential vulnerability and a fundamental flaw inside the protocol’s design.

The fundamental principle they mentioned here is called crypto key routing, which makes use of a crypto key routing table. What we have to understand about the core of wireguard is that all devices in its virtual private networks are called peers, with no exception. So naturally we assign a virtual source IP to them and in the “routing table” we assosiate them with public keys. This defines one attribute of our wireguard configuration. Another attribute that is equally important is the interface. Here we declare its private key and listening port. Endpoints are also configurable, and they define the destination IP of your packets (typically in a WAN context). This is usually done in a client configuration.

Here’s what it might look like:

[Interface]

PrivateKey = gI6EdUSYvn8ugXOt8QQD6Yc+JyiZxIhp3GInSWRfWGE=

ListenPort = 21841

[Peer]

PublicKey = HIgo9xNzJMWLKASShiTqIybxZ0U3wGLiUeJ1PKf8ykw=

Endpoint = 192.95.5.69:51820

AllowedIPs = 0.0.0.0/0This is a typical client configuration, but it would look pretty much the same on a server, we’d only remove the endpoint. You can now see how the allowed IPs act as some sort of access control list when receiving packets, and as a routing table when sending packets (note you can set multiple AllowedIPs!!). This design decision has been made to implement an authentication mechanism that makes use of a handshake. As I’ve previously stated, we won’t get into it now. Rather we’ll focus on their introductory statement which only mentions the relationship between the public key and the tunnel source IP address.

The way this works is that when a recipient peer gets the packet, the first step it takes is to look at the virtual source ip, and conditionally check if it matches one that is inside its allowed IPs list. It then goes on to check if the public key is correctly associated to that IP. This is the basis of wireguard authentication and what gets built upon with other layers of security in the rest of the whitepaper!

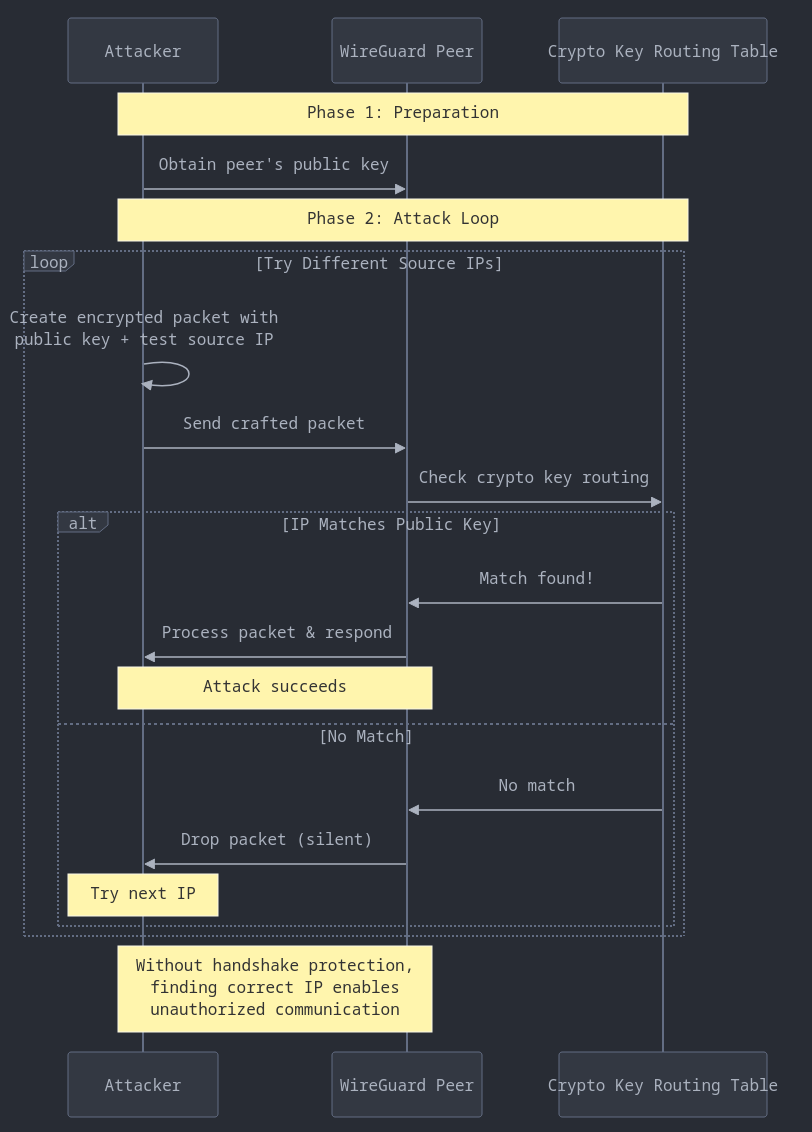

And so this is exactly what led me to believe, that after the acquisition of a peers public key, an attacker could theoretically create interfaces with multiple source IPs, with the purpose of finding one that is inside the target peers AllowedIPs list (by enumerating through a list for example). And use that same public key, to encrypt data and send it to the target peer. That would effectively allow him to send whatever he wants to his computer! But that idea got shut down real quick as I kept on reading haha.

Endnotes & Future Exploration

This semi-deep dive represents the beginning of my journey into understanding WireGuard’s architecture. The whitepaper covers significantly more ground, but I’ll be exploring these advanced topics in upcoming pieces. The goal here was primarily to establish a solid foundation before implementing WireGuard.

If you know this stuff better than I do, feel free to reach out to me on X @pindjouf to discuss, correct, or expand on any points made here.